Hodling and the cryptocurrency revolution

Are you hodling? No, that’s not a typo – it is millennial-speak for what you do if you are a true believer in the cryptocurrency revolution. Look it up. I wouldn’t describe myself as old, but I’m certainly old enough not to be automatically in tune with what motivates millennials. However, you can hardly open a newspaper these days without some notable individual passing comment on cryptocurrencies, and they even seem to be going mainstream now that bitcoin has been made legal tender in El Salvador – you can buy residency there for 3 bitcoin. It seemed therefore like a good moment to try and get at least a vague understanding of what cryptocurrencies are, as I suspect that many of the readers of this newsletter will be as confused as I am on the topic, so let’s see what we can discover. I will be focussing particularly on bitcoin, as the main example of a cryptocurrency, but do be aware that bitcoin is only the most prominent out of the estimated 10,000+ cryptos out there.

Everything you don’t know about money, combined with everything you don’t know about technology

This was a tongue-in-cheek definition of cryptocurrencies that I heard not so long ago from an asset manager, but it kept coming back to me every time I saw cryptos mentioned in the press.

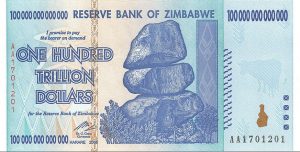

Once upon a time, “money” essentially meant some amount of precious metal, generally in the form of a coin which was easily recognisable. Then we evolved to a situation in which we used banknotes to represent an underlying amount of precious metal, and finally we arrived at where we are today, where any link with precious metals has been definitively severed in favour of fractional reserve banking and “fiat” currency controlled by sovereign states – the “fiat” is Latin, meaning “let it be done”, and is the essential expression of our concept of legal tender: something is money not because it has any intrinsic value, but because the law says it is. These fiat currencies rely on trust in the good economic management of the issuing countries, and we can all think of notable examples of where bad management has left fiat currencies broken. I have a 100 trillion dollar note issued by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe in my office as a reminder of the importance of sound currencies.

Not many of us could properly explain a fiat currency system and the interactions between bank deposits, bank lending and central bank reserves and, as a result, many find it tempting to say that even major currencies like the US dollar and the euro have little intrinsic value due to the fact that their supply is essentially unlimited. To a certain extent, cryptocurrencies were born out of a lack of trust in fiat currencies (even the “good” ones) and the desire to make money something more regulated (not in the sense of having more government oversight, but rather of wanting precise rules and limitations on the amounts of currency in circulation). In order to be worth something, so the reasoning goes, the supply must be limited and it must be difficult to create – hence the parallels that are sometimes drawn between cryptocurrencies and precious metals.

Not many of us could properly explain a fiat currency system and the interactions between bank deposits, bank lending and central bank reserves and, as a result, many find it tempting to say that even major currencies like the US dollar and the euro have little intrinsic value due to the fact that their supply is essentially unlimited. To a certain extent, cryptocurrencies were born out of a lack of trust in fiat currencies (even the “good” ones) and the desire to make money something more regulated (not in the sense of having more government oversight, but rather of wanting precise rules and limitations on the amounts of currency in circulation). In order to be worth something, so the reasoning goes, the supply must be limited and it must be difficult to create – hence the parallels that are sometimes drawn between cryptocurrencies and precious metals.

A lump of gold sitting in a vault somewhere has value simply because we think it has value; up until the time that you find a practical use for that gold, its value is dictated by that vague idea that come (almost) what may, at least it will always be there. Not an amazingly intelligent argument, it must be said, but better than many things that finance has come up with over the years. The basic reason for abandoning the link between money and precious metals was that the supply of commodities like gold or silver were subject to vagaries that had little to do with the overall economic situation, so bullion failed to keep up with our economic growth.

As far as bitcoin is concerned, it is very clear that scarcity is central to its functioning given that it has been set up to have a maximum number of 21 million units. As of today, there are roughly 18.7 million bitcoins that have been created, but the number effectively available for transactions is much lower, due to the fact that many people hodl, and also due to the fact that a large number of coins have been lost (I have read estimates of 20% of the total in existence). You see, if you have a bitcoin, you better make sure you keep hold of the codes that allow you to access it, because there is no “lost password” function if you don’t. Losing the codes is the digital equivalent of throwing your gold bars into the Mariana Trench; they don’t cease to exist, but you will find it all but impossible to recover them. It is worth noting that whilst the scarcity value of bitcoin may be beyond doubt, the fact there are so many other cryptocurrencies around should give pause for thought about the scarcity of the category as a whole.

As far as bitcoin is concerned, it is very clear that scarcity is central to its functioning given that it has been set up to have a maximum number of 21 million units. As of today, there are roughly 18.7 million bitcoins that have been created, but the number effectively available for transactions is much lower, due to the fact that many people hodl, and also due to the fact that a large number of coins have been lost (I have read estimates of 20% of the total in existence). You see, if you have a bitcoin, you better make sure you keep hold of the codes that allow you to access it, because there is no “lost password” function if you don’t. Losing the codes is the digital equivalent of throwing your gold bars into the Mariana Trench; they don’t cease to exist, but you will find it all but impossible to recover them. It is worth noting that whilst the scarcity value of bitcoin may be beyond doubt, the fact there are so many other cryptocurrencies around should give pause for thought about the scarcity of the category as a whole.

The creation of bitcoin is one of the things that I struggle with the most – it is commonly called “mining”, in an evident attempt to draw a parallel with precious metals, even though the mining in the case of cryptocurrencies is entirely digital. Essentially, they are discovered by computers contributing to the distributed ledger that monitors all bitcoin transactions. The only explanation of bitcoin mining that has made some sense to me so far is to consider it in terms of a triple-entry accounting system: There are two parties who record a transaction and this is then sealed into bitcoin transaction records by a third party that verifies it through its mining activities (and receives a reward for doing so). Mining, in the world of bitcoin, is technically called a “proof of work” and allows a participant in the network to be rewarded by participating in the distributed ledger and crunching the enormously complicated numbers that guarantee the transactions that have been recorded. This ledger, also known as the blockchain, belongs to everyone and no-one, rather like the internet itself, and it exists in order to eliminate the risk of someone being able to spend the same bitcoin twice. No, I don’t really understand it either.

It is also said that bitcoins and their transactions are “immutable” – I suppose to the same extent that precious metals are immutable. But does this really make any sense? Aside from the apparent lack of ability to hack the blockchain today, can we really be confident that in a thousand (or a million!) years bitcoin will still be unhackable and attractive to a sufficiently large community of people? Perhaps this is more of a philosophical question than anything else, but us humans do get wrapped up in the idea that the big issues of today are the big issues for all time. I suspect our distant descendants, assuming the human race is lucky enough to survive, will become interested in many things beyond bitcoin or cryptocurrencies in general. In this context, the best parallel to draw is with technological innovation: today, not many people are interested in steam engines or dirigible balloons, once important technological developments, and the same may be true for bitcoin in a few decades. For bitcoin to enjoy any value at all, it is dependent on the bitcoin community continuing to support it through time. It would be highly unwise to think that nothing will ever come to supplant it, because human experience with other technologies suggests that better things are always on the horizon. The same cannot be said for precious metals, which may wax and wane in terms of community interest, but do not depend on community interest for their existence. My gold bar will still be there in a thousand years if it is kept safe, regardless of what people might think about it. What might happen to it over the course of a million years is a question I find rather difficult to ponder, but it’s probably fine for the next few thousand.

In all of this, the real evolution may be arriving shortly, and it is not to be found amongst the many new variations on the bitcoin theme that have come into existence. Many have looked upon cryptocurrencies as a way of thumbing one’s nose at traditional financial structures – no more central banks and traditional bank accounts for me please! Yet the governments of this world are not going to give up the privilege of being able to issue national currency without a fight, and it could be that they will try to beat the cryptos at their own game. Some cryptos, known as “stablecoins” are backed by a given fiat currency, but it has been suggested that the most appropriate issuers of such coins are the central banks themselves. One idea is that each of us could end up, as of right, with our own account at the central bank of the nation we live in. If this were to happen, then bank runs would no longer be an issue and commercial banks would have to reinvent their business models, at least in part. Presumably physical cash would become a thing of the past. This is not speculation on my part – the ECB is publicly discussing the benefits of digital coins and the Bank for International Settlements – the central banks’ central bank – has even commented that this is “a concept whose time has come.” The full BIS report is available here for anyone who is interested.

In all of this, the real evolution may be arriving shortly, and it is not to be found amongst the many new variations on the bitcoin theme that have come into existence. Many have looked upon cryptocurrencies as a way of thumbing one’s nose at traditional financial structures – no more central banks and traditional bank accounts for me please! Yet the governments of this world are not going to give up the privilege of being able to issue national currency without a fight, and it could be that they will try to beat the cryptos at their own game. Some cryptos, known as “stablecoins” are backed by a given fiat currency, but it has been suggested that the most appropriate issuers of such coins are the central banks themselves. One idea is that each of us could end up, as of right, with our own account at the central bank of the nation we live in. If this were to happen, then bank runs would no longer be an issue and commercial banks would have to reinvent their business models, at least in part. Presumably physical cash would become a thing of the past. This is not speculation on my part – the ECB is publicly discussing the benefits of digital coins and the Bank for International Settlements – the central banks’ central bank – has even commented that this is “a concept whose time has come.” The full BIS report is available here for anyone who is interested.

Much has also been said about the potential of the blockchain – essentially the network that runs bitcoin – to revolutionise everything from banking to contracts. We’ll just have to wait and see how all of that shakes out, but it is clear that there are numerous technologies being developed and brought to bear on finance and commerce and it’s by no means clear that blockchain technology is the only answer. In any case, even if the blockchain network is valuable, this says nothing about whether any given cryptocurrency that relies on it has value.

As I suppose must be obvious by now, my research for this article hasn’t convinced me that cryptocurrencies are a good place to speculate (please let’s not use the term “investment” in this context!) – and certainly I see no reason why investment in this sort of asset should supplant traditional assets in an investment portfolio. As boring as it may sound, what really counts in investment is not jumping on that latest bandwagon, but planning one’s affairs properly whilst having a disciplined approach and a long-term view.

As a final point, for any Italian residents, please also be aware that bitcoin investments and gains deriving therefrom are subject to declarations and taxation in Italy – you may think your cryptos are 100% anonymous, but I wouldn’t be betting on it.