I’m not entirely sure if I’m writing my first Spectrum article at what amounts to an auspicious or inauspicious time. Certainly I didn’t imagine that I would be writing it in my current circumstances, which essentially amount to being under house arrest. Many of the people reading this will be in similar circumstances to me, and those of you who aren’t risk becoming so over the coming weeks.

Generally on these occasions we feel the need to say such things as, “I hope you are all safe and well”, but I think this goes without saying. All of us have some friend or family member who is in the high risk category, so what I will say is: for those of you at high risk, be careful. For the rest of us, let’s be aware that things could be worse for us personally and keep a lookout for people who may need some help.

It would have been nice to have started out by writing something positive about Italy, but the current situation brings into sharp focus the vulnerability of the Italian economy to external shocks. The debt situation in Italy propagates a fragility that becomes disturbingly apparent at times like these. Put simply, when you are up to eyeballs in debt in normal times and a crisis hits, you don’t have any flexibility to withstand the shock.

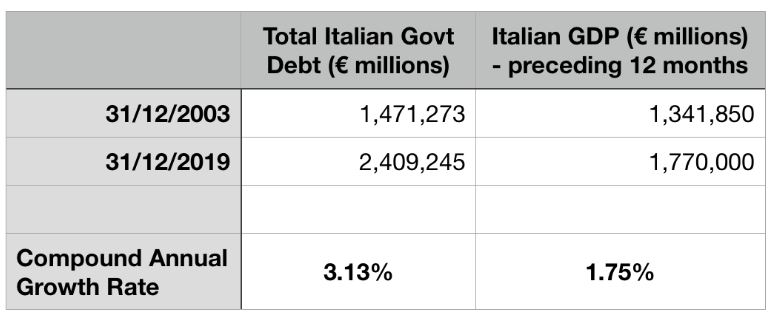

Since I moved to Italy in 2004, this has been the evolution of the debt situation:

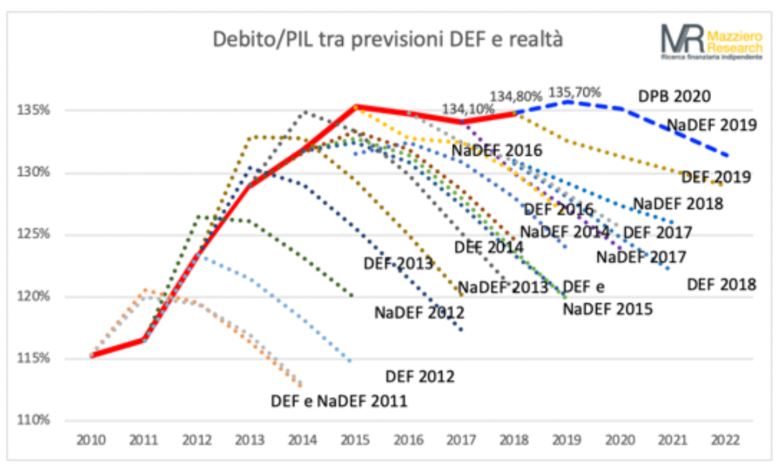

I find it astounding that Italy has managed to accumulate almost 1 trillion euros of extra debt over the last 16 years, a period in which GDP has increased less than half that amount. Each and every initiative to realign the government accounts has failed miserably, as evidenced by the graph below (source: www.mazzieroresearch.com):

What this graph shows is the annual budget forecasts (and updates, when announced) for the evolution of the Debt/GDP ratio over the years following the forecast (these are the dotted lines), compared with what has actually happened (the solid red line). The bold blue dotted line is the current forecast, but it’s fairly clear that the current crisis will lead to a drastic change in this.

How much of a change is an interesting question…

Let’s consider that the latest declarations from the president of the Confindustria business lobby group, Vincenzo Boccia, estimate that roughly 70% of Italian productive activity is closing, so something like 100 billion euros a month of lost GDP for the duration of the current period of “lockdown”. All of this leads to the certainty that tax receipts will drop off a cliff, either because no tax is due (or some kind of “holiday” is given), or because companies and individuals simply don’t have the money to pay. This is happening at a time when the government will be called upon to increase spending, both to respond to the direct costs of dealing with the healthcare emergency and to give some support to businesses and workers (through cassa integrazione (temporary support for idle employees) or support payments).

So if we assume a drop of 70% in tax receipts and an increase of 20% in government expenditure compared with 2019 levels, you get an annual deficit for 2020 of 550 billion euros (in 2019 the deficit was 67 billion). So we are possibly faced with a 40 billion euro hole to fill each month compared to Italy’s normal situation. Almost 700 euros per capita, per month. If the whole year continues this way, we end up with a Debt/GDP ratio of around 165%, and this is on the generous assumption that GDP rebounds immediately to 2019 levels.

Given the above, it is not surprising to hear renewed suggestions that the EU should start issuing European bonds. Over the years, since the financial crisis of 2007/08, the weaker countries of the EU have sometimes tried to suggest that true European bonds should be issued by the Union, which would have the effect of explicitly making the more virtuous members (especially Germany) jointly and severally liable for debts of more profligate members such as the PIIGS countries.

Given the above, it is not surprising to hear renewed suggestions that the EU should start issuing European bonds. Over the years, since the financial crisis of 2007/08, the weaker countries of the EU have sometimes tried to suggest that true European bonds should be issued by the Union, which would have the effect of explicitly making the more virtuous members (especially Germany) jointly and severally liable for debts of more profligate members such as the PIIGS countries.

This time, it is being suggested that these bonds carry the alluring although somewhat morbid title of a “Coronabond”. Good luck getting that one past the Germans, even if the proposal is only to issue such bonds as a temporary measure to generate support for those economies most heavily affected by the current crisis. Most politicians understand instinctively what economist and Nobel prize winner, Milton Friedman, once said: there is “nothing so permanent as a temporary government programme”. Once you’ve issued your first European Bond, how will you be able to say no next time?

So what does this terrible situation mean from a financial perspective for your average Italian resident with some savings and investments? Given that most of us have a bit more time on our hands than usual, it might be an idea to have a proper look at your situation and ask some of the following questions, although you must only do so without panicking and without jumping to hasty conclusions:

- How are my investments holding up compared with the risk expectations that I had at the time the investment was made? If, as is probable, there are some unrealised losses in my portfolio, am I comfortable that the current situation isn’t putting my overall financial situation at risk?

- Where and how do I hold my assets? If they are all deposited in one bank or in one country, is it worth looking at diversifying my country risk? Banks are generally only considered as strong as the country they are based in (and they generally hold piles of government debt), so credit-rating agencies will not give a higher rating to a financial institution than that given to the sovereign nation it is based in.

- If I have been a cautious investor up until now or have hoarded cash, should I look at increasing risk given the falling values in the market?

- If I have invested aggressively and am now sitting on losses, how are my nerves holding up and am I framing any discussion on the subject in the right way?

If any of the above questions resonate with you, then now might be the time to have a chat with me. At the minimum, it can be reassuring to discuss any situation in which you find yourself unsure of the consequences. My colleagues and I can help to bring focus to the important issues and cut through the noise generated by the crisis. Peace of mind can only come through analysis and understanding. Hope is not a strategy and neither is reacting on gut feelings or emotions generally.